Description

THE RED LIST

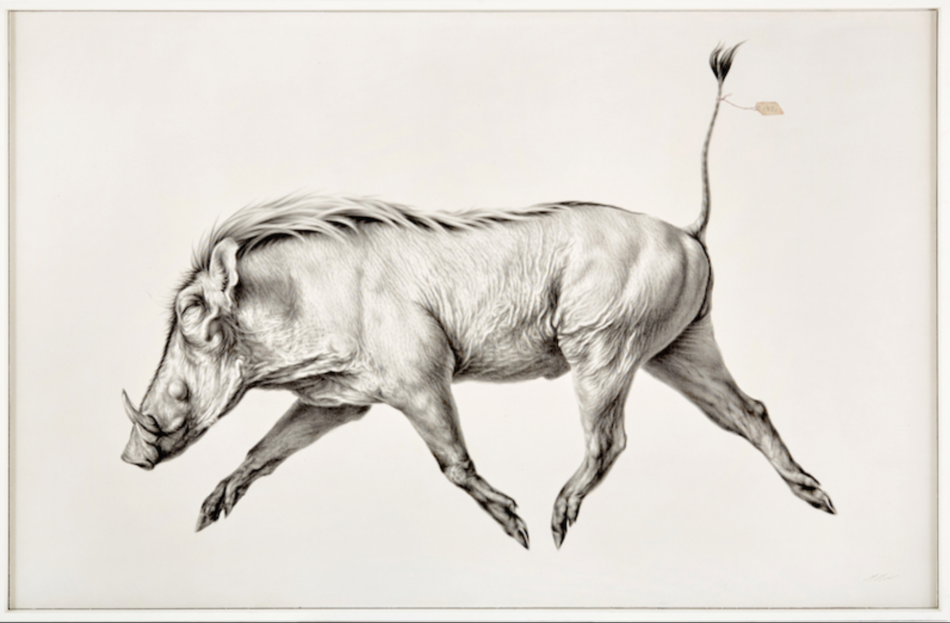

Hypotype – Cape Warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus aethiopicus IUCN Extinct

Charcoal on cotton canvas

122 x 190 cm

$ 11,500

Recently on exhibition at Melbournes Metro Gallery, now displayed at Allpress inc

Phacochoerus aethiopicus aethiopicus, originally native to South Africa, this subspecies became extinct around 1871. Cape warthog specimens held in museums lack locality records and the full extent of the Cape warthog’s former distribution remains unknown. There is no mention of this subspecies being obtained after 1860. The Cape warthog and the Dessert warthog are very similar in appearance, one difference is a lack of functional incisors.

Nowadays we overuse the word ‘Icon’. Once it stood for something very powerful: a sacred object that existed at the nexus between the Human and the Divine, but we have debased the word. Instead we have Aussie Icons, and ‘iconic’ celebrities and sport stars.

Mali Moir on the other hand, in this series of works titled ‘The Red List’, has provided for us a set of icons imbued with much of the aura of traditional religious images. The subjects of ‘The Red List’ could indeed be described as the saints and martyrs of the animal kingdom, and like the saints of medieval times, each has been portrayed with an emblem which provides some commentary either about the tenuous existence of the species, or the circumstances of its passage into oblivion. Moir’s drawings have a monumental quality. The sfumato technique which she employs makes the creatures appear to float on the surface of the paper. Their corporeality and tactile appearance is almost sculptural, as if they are the stelae from the pediment of some wondrous Temple of Nature. Serene they might be, but they are also heart-achingly poignant. Here are wonderful beings that we have wasted; which have either moved beyond the point of recall or which have arrived, through our actions or negligence, at the very brink.

A device has been used which might not be immediately obvious but which imbues the group of works with powerful symbolism. The creatures which are gone for ever face left and backwards in time. We will never see them or encounter them again in the flesh.

Among them, the Thylacine, a unique apex predator that we in Australia literally blasted out of existence. Who has not seen the shaky movie footage of the last living specimen pacing in its prison, and not felt the mire of guilt?

Then there is the Dodo – that ridiculous and ungainly pigeon – incapable of fear and flight… wantonly consumed by rapacious sailors. This bird has become a byword for that which is dead and irretrievable. Yet another bird, stately and fantastical, hunted and consumed beyond recovery: the Moa, which had already become the stuff of Maōri legend before the era of Tasman and Cook.

This ‘litany of saints’ continues on but now the key signature changes and perhaps we are given a glimmer of hope. Other animals face right, forward and looking ahead to the future. These are the ones that still grace our skies and forests. The Californian Condor, so nearly wiped out that the survivors had to be captured and placed in a controlled breeding program. Magnificent predators imprisoned for their own survival, and Critically Endangered, as their red tag tells us.

The nobly horned Markhor of Central Asia is depicted in a couchant position like some beast of medieval heraldry. Its survival is not just important for its own sake, but to ensure that the equally threated Snow Leopard, which feeds upon it, also survives.

Mali Moir is probably best known in Australia for her extraordinary body of documentary illustration in the field of botanical research. The works in this exhibition are clearly rooted in this natural history tradition, but whereas Moir’s botanical productions are imbued with a certain degree of scientific detachment, these current works deliberately set out to move us.

We have destroyed so much that was full of wonder and beauty. Moir is telling us here that it is time to draw a line in the sand; time to act to end the extinctions and pull back from further catastrophe.